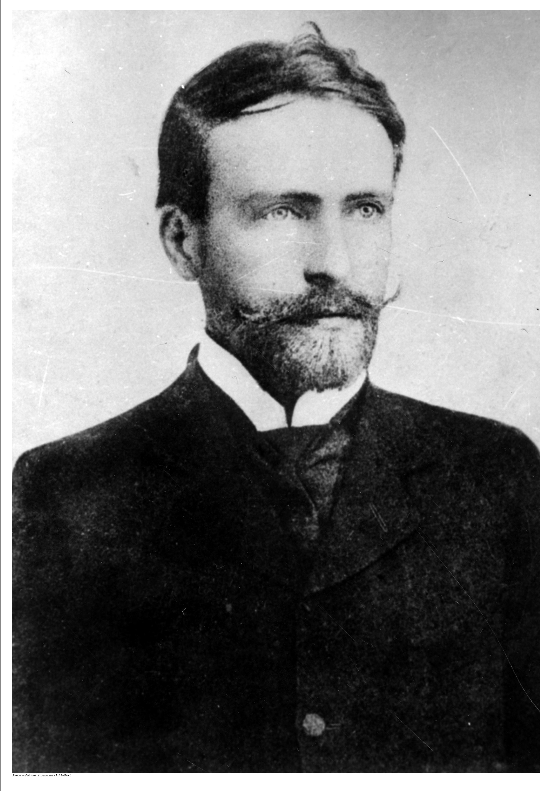

Stanisław Wyspiański (1869-1907) is one of the most versatile artists of the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. His message and own recognisable style are an absolute part of Polish culture and art today. Wyspiański was an accomplished artist as he was active in various fields of art, and in each, he always pursued avant-garde techniques that influenced a large number of artists. He was not only a painter and created stained glass windows, he also designed furniture, posters, books, and magazine covers. His literary work is just as important: he was a well-known playwright and poet. His imagination and creative invention not only crossed artistic boundaries but also posed a challenge for next generations. As an artist, he was influenced by Antiquity and the Middle Ages. His art dealt inventively and historically with issues of national and religious identity. Let’s dive into his life to learn a bit more about this polyvalent artist.

Wyspiański was born and raised in the late nineteenth century in Kraków, which was then a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His upbringing in that location and community had a significant influence on the development of his creative imagination. At the base of the Wawel Hill, where his father, the artist Franciszek, had his atelier, stood a cathedral that was replete with artefacts from the former Polish state and a royal castle that was, at the time, an Austrian army garrison.

He went to Sainte-Anne secondary school for his studies. It was one of the few institutions that allowed instruction in Polish under the Habsburg rule. Polish literature and history were taught in great detail which has had a great influence on his later work. While still a student, he helped restore St Mary’s Church and contributed to the inventory of Galician monuments (Galicia was at the time a region, today divided between western Ukraine and eastern Poland). Among his discoveries was a wooden statue of Our Lady of Częstochowa from Podkarpacie, dating back to the fifteenth century, found in the village of Kruzlowa. The National Museum in Kraków presently houses the so-called Madonna from Krużlowa. This work must have encouraged him to take a more personal look at Poland’s heritage as well as increasing his sensitivity to detail in fine arts. His unique imagination made him view the work (whether he was looking at it or creating it) as a fragment of a historical event.

Together with fellow Polish painter, Jozef Mehoffer, he constructed 36 stained glass windows as part of his work with Jan Matejko on the conservation of St Mary’s Basilica. They both also created curtains for Kraków’s Juliusz Slowacki Theatre. His trip to Paris helped him get free from Matejko’s direct influence, but he never lost the intellectual and creative inspiration he received from the well-known Polish painter. He left for four years, came back to Krakow, and started working right away.

In the years 1890–1918, the city of Krakow grew from a provincial centre to the spiritual and artistic capital of the country. It became the cradle and then the centre of Polish modernism. ‘Young Poland’ (Młoda Polska), an artistic movement, was a protest against the standardisation and technicisation of social life and bourgeois customs. The meeting places of Krakow’s artists were, of course, the cafes. The most popular was Café Paon. After its closure, the artists, including Wyspiański, moved to Jama Michalika (still open today), where Krakow’s first literary cabaret, Zielony Balonik (the Green Balloon), was born.

In 1894, Stanisław Wyspiański obtained the order for the polychromes and stained glass windows of the Franciscan Church, which would turn into his greatest work of art. The artist’s detailed interior murals, which include vibrant flower patterns to honour St Francis’ love of the natural world, are certainly impressive, but the most striking feature is the enormous stained glass window above the choir named ‘God in the Act of Creation.’ Wyspianski also made other contributions to the Franciscan Church, including six stained glass windows in the presbytery and polychrome with an eye-catching wildflower motif.

Theatre was another aspect of Wyspiański’s visual arts activity: he produced plays by foreign artists, directed plays of his own, and created stage sets. He was regarded as the founder of the so-called Polish Great Reform of Theatre because of his avant-garde perspective. The quantum leap in the history of Polish theatre was the staging of The Wedding according to his own production guidelines. The first representation took place on 16 March 1901 in the Municipal Theatre in Kraków. Although it was written at the very start of the twentieth century, The Wedding (Wesele) is regarded as the most significant and finest Polish play of the 1890–1918 period. Some of its images, such as the ‘golden horn’ (a metaphor for lost hopes) and the ‘Straw Man dance’ (a symbol of overpowering obsession with inaccurate ideals), were terms that became part of the Polish lexicon.

‘Here lives Stanisław Wyspiański, who does not wish to be visited.’

Wyspianski centred his creative interests around the human condition. He was an expert at drawing precise portraits. He painted people from his very close circle: his wife, his children, or his friends. He sketched with vivid, strong lines. He focused essentially on the model’s facial expressions and emotions. Wyspiański’s key theme was freedom of the individual.

In addition, Wyspiański was a devout city official involved in municipal issues and a supporter of cultural heritage preservation. He authored critical journalistic articles and was interested from an early age about the preservation of architectural and artistic masterpieces. That is why he was one of the founders of the Society of Friends of Kraków History and Heritage, which was founded in 1896.

Rumour has it, he lived with his family where his studio was also situated and on the door a sign said: ‘Here lives Stanisław Wyspiański, who does not wish to be visited.’

He passed away at 38 years old. His funeral took place in Kraków which turned into a national day of mourning. Wyspiański was buried in the Crypt of the Distinguished in Skałka church. In honour of his 100 years of disappearance, the Polish Sejm proclaimed 2007 as the Year of Stanisław Wyspiański.

Nowadays, Wyspiański is still an inspirational artist from Polish history. The National Museum in Krakow has the largest and most valuable collection of his works (around 1 000 items). We are talking not only about paintings, but also single sketches, pounced drawings and stencils, as well as furniture, his library consisting of nearly 600 books (some with the artist’s notes and first editions, as well as a huge manuscript legacy), poems and plays, letters, documents, family pictures and personal mementoes.

Start your journey in the Extinguished Countries!

Get a free chapter from our first guidebook “Republic of Venice” and join our community!