The Democratic Women’s Association’s protests against women’s inferior earnings in 1848 marked the start of the Austrian women’s movement. It was quickly dissolved after being ridiculed by many men and because women were not allowed to join associations explicitly political due to the 1867 Law on Assembly and Association. Its spirit reappeared in new associations committed to social and educational pursuits.

Many women from Austria and Hungary were actively fighting for their rights in organisations; the Autonome Österreichische Frauenhäuser (AÖF, Association of Austrian Autonomous Women’s Shelters) in Austria and the Feministák Egyesülete (FE, Hungarian Feminist Association) in Hungary were the biggest ones. Unfortunately, we won’t be able to name all of these women so if you’re interested in this topic, we suggest you read “Shifting Voices, Feminist Thought and Women’s Writing in Fin-De-Siècle Austria and Hungary” (2008) by Agatha Schwartz, which is an essay gathering many feminists’ writings concerning their rights.

In the 18th century and under Emperor Joseph II, women in Austria and Hungary were given several privileges, including the ability to work without their husbands’ consent and possess and manage their own property. However, as feminists of the fin de siècle pointed out, reality was typically far different from what the law intended due to family and society expectations. Even the little privileges that women in the middle and upper classes did have were not well known to them. It required the initiative of courageous women and the influence of women’s organisations to assert those rights and work towards the realisation of others at the end of the 19th century.

The fight for suffrage was unsurprisingly less noisy than the Suffragettes’ one in the UK but it was still very present. The feminists’ movement was almost more important in Hungary than it was in Austria. This is especially noticeable in cities, at a local level. Women gathered at feminist events and journalists covering them mentioned their names in articles. This allowed them to create a feminist network in the years 1890–1900.

The FE focused more on concrete activism. They raised awareness of the issue by creating and distributing posters, postcards, special stamps, and newspaper articles. They also hosted a lot of open forums where the topic of women’s suffrage was raised. The FE believed particularly in ‘equal political rights for both sexes’.

The majority of these feminists were Jewish because they came from the bourgeoisie. They were educated and had a certain interest in social causes, which was not the case for women from the aristocracy or from modest backgrounds (who did not have access to education). There were also right-wing feminists, who promoted traditional values through charitable work. These women were ranging from more conservative to more progressive forms of feminism and were often balancing between a cultural and a radical position. They had three major goals in their movement: the fight for women’s higher education, the fight for political rights, and the fight for a change in sexual standards and norms. Most of these feminists were advocating for their rights as long as it would not affect traditional values: “emancipation may bring a woman professional fulfilment as long as it does not violate traditional gender roles” (Schwartz, 2008). Except for Marie von Troll-Borostyáni.

Marie von Troll, who later on changed her name to Irma, was born in Salzburg in 1849. She received an excellent education. She studied music in Vienna but had to abandon her dreams of becoming a pianist. Under the alias Leo Bergen, she started publishing sketches in different publications. She travelled to Hungary, where she resided with an aristocratic family as a piano instructor. Three years later, she moved to Budapest, where she eventually married the Hungarian writer Nándor von Borostyáni in 1875, who was very supportive of her writing career. Along with literature, Troll-Borostyáni wrote a number of important theoretical works related to the Austrian women’s movement. Throughout her life, she published nineteen books and countless articles in newspapers and periodicals about women’s rights. She was straightforward, which was not always appreciated by her peers. In addition to being a radical thinker, she also disobeyed social norms by cutting her hair short, dressing in men’s shirts and jackets, smoking cigars in public, and being an avid sports fan. A street in Salzburg was named after her in 1996.

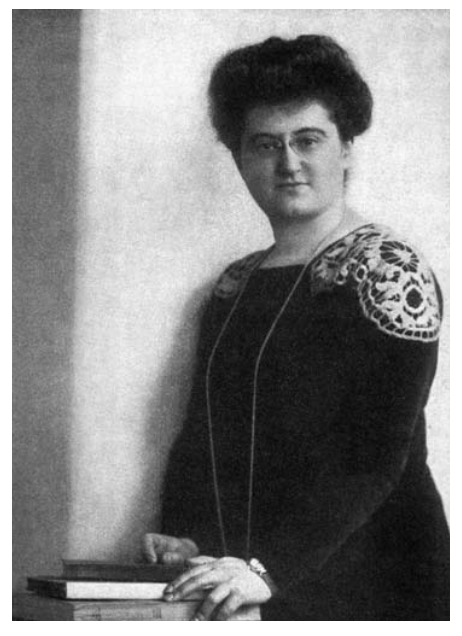

I would say Rózsa Schwimmer, known abroad as Rosika Bédy-Schwimmer. She was born in 1877 in Budapest. She worked as a bookkeeper and contributed to the establishment of the National Association of Women Office Workers (Nőtisztviselők Országos Egyesülete). She was its president from 1897 to 1912. She was one of the founders of the FE and was highly active on a global scale as a writer and speaker due to her knowledge of nine languages.

At the time, Hungarian middle-class women had been organising, but they were not yet working together towards one common goal. The Feminist Association, of which Rosika Schwimmer would become a founding member, was not established until 1904. This association targets girls’ education as the main cause for women’s economically unequal status. According to Schwimmer, girls’ education only prepares them for ‘dependence, powerless attachment and a need to seek support in others’ (Bédy-Schwimmer, 1907a, 9).

In addition to co-organising the 7th Congress of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) in Budapest, she was the editor of the magazine A nő és a társadalom. She was chosen to serve as the IWSA’s corresponding secretary in 1913 so she relocated to London the next year. She stayed in London after World War I broke out and started organising pacifist and feminist leaders. She travelled to the US and met with President Wilson and Secretary of State Jennings, pleading them to halt the war. Additionally, she represented Austria-Hungary at the 1915 International Congress of Women in The Hague, where she was a key organiser and leader.

Schwimmer spoke with representatives of various countries in London, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Rome, Berne, and Paris with an effort to bring the war to an end. The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom elected her vice president. She was appointed Hungary’s ambassador to Switzerland under the Károlyi administration. Károlyi was overthrown by Béla Kun’s Communist government in 1919, and Schwimmer escaped to Vienna in 1920 to avoid the anti-Semitic Horthy administration that followed. She immigrated to the United States in 1921. She was labelled a dangerous radical and accused of being a part of a Jewish plot, a German spy, and a Bolshevik operative. Her citizenship application was turned down. Even though she lived in the US until her death, she was officially a stateless person. She was nominated for the 1948 Nobel Peace Prize by a number of countries, but she passed away prior to the winner being announced. That year, there was no award conferred.

Not much remains of feminist activism during the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The pioneers and activists have been forgotten. There was an attempt to remember their names or image through the printing of stamps or bills, but it was not successful. Despite the emergence of a conservative women’s movement, women’s rights did not become part of the political agenda until after 1945. Most of the radical feminists who wrote many essays or even novels regarding women’s rights are largely unknown today even in their respective countries of origin.

Start your journey in the Extinguished Countries!

Get a free chapter from our first guidebook “Republic of Venice” and join our community!