Kerosene, or paraffin, is a combustible liquid derived from petroleum. Its discovery is generally attributed to Canadian geologist Abraham Gesner who distilled kerosene from bituminous coal and oil shale in 1846. To obtain kerosene distilled from oil, however, one has to wait a few years and travel to the other side of the world: to Habsburg Galicia. In this region where oil production boomed at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, two pharmacists managed to distil kerosene from oil and created the first kerosene lamp.

In 1852 Piotr Mikolasch, the owner of “Under the Golden Star,” one of the greatest and largest pharmacies in Galicia, instructed Johann Zech (or Jan Zeh) and Ignacy Łukasiewicz to turn oil into alcohol. The two pharmacists conducted thorough research for several months, but they were having little success. Up until the day they discovered an unfamiliar substance that burned brightly and had no smell. It was safe to use and hygienic because there was little to no smoke. All previous attempts to create anything like it have failed; the only products available were not popular as they were explosive and made a lot of smoke. The people of Lviv cautiously avoided the oil-fired street lights for fear of being stained by smoke oil, which ruined all of their clothes. But the new substance was different.

Johann Zech and Ignacy Łukasiewicz created a lamp that was much cleaner to use indoors as well. In March 1853 they displayed it in the pharmacy window, but it was not that popular among Lvivians. It was actually doctors who sparked people’s interest. In July of the same year, surgeons at the city hospital attempted to do emergency surgery using kerosene lamps. This proved that this new invention was safe and hygienic and as a result, oil lamps gained popularity, especially as natural gas was too expensive to compete with kerosene. Then, every home in the late 19th and early 20th centuries had a kerosene lamp. There were many lamps to choose from, ranging from affordable, basic and sturdy to highly ornamented and unique pieces that were only accessible to the wealthy. They provided light to both public and private areas and were frequently associated with luxury and flair.

The invention was recognised around the world. Johann Zech obtained the diploma from the Vienna Patent Office in 1853. The invention was defined as a technique of cleaning oil for use in lighting and heating. At the Munich World Exhibition a year later, Zech received a certificate for perfect oil cleaning. This was not Zech’s first invention. In 1850, he received an honour for a method of reusing steam in a steam engine, and later received a whole series of other patents.

(Today the pharmacy is a pastry shop!)

The destiny of the innovators then diverged. Zech set up a little laboratory and a store, where his wife and her sister sold oil to remove stains from clothing and kerosene for lighting. One day, one of the kerosene barrels that the business received was damaged. Some liquid leaked and when a pedestrian flung a lit match out of nowhere, it immediately set a fire that swept throughout the shop. Zech’s wife and sister and two ladies who were purchasing kerosene perished in the fire. Following the catastrophe and further issues in his life, Zech retired from the oil business in the 1870s. In Lviv, there is a monument that honours him and shows Zech sitting on a bench. It is sometimes mistaken for the one of Łukasiewicz, which depicts the pharmacist pointing at his colleague while leaning out of a building’s window.

Łukasiewicz wasn’t only a great pharmacist, he was also a Polish nationalist and social worker. In 1840, he became a member of the Polish Democratic Society, an illegal political organisation that called for an uprising against the Austrian authorities. He provided fundings for assistance to numerous refugees and supported the January Uprising in 1863. Because of his political involvement, he was arrested many times. In 1866, he helped establish the first insurance company in Poland, as well as a workers’ union known as “Kasa Bracka,” which helped to provide financial assistance to the most vulnerable.

“This liquid is the future wealth of the country, it’s the wellbeing and prosperity of its inhabitants, it’s a new source of income for the poor, and a new branch of industry which shall bear plentiful fruit,” he said regarding kerosene.

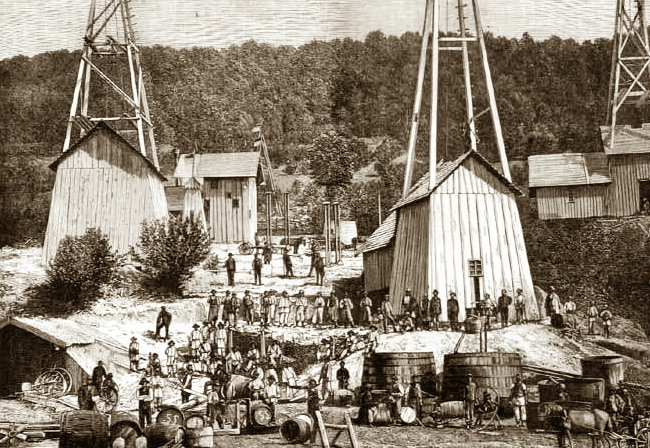

In 1854 Łukasiewicz, with Tytus Trzecieaki and Karol Klobassa established some of the world’s first oil wells in Bóbrka (today it is a museum), and two years later he was a partner in the first Polish oil refinery which opened at Ulaszowice.

He also established the National Oil Society and arranged the first Oil Industry Congress in 1877. He was elected to the Galician Sejm and was one of the most well-known merchants of his day, having amassed one of the greatest fortunes in Galicia. He then became a regional benefactor and founded among other things, a spa resort in Bóbrka, a chapel in Chorkówka, and a church in Zręcin. When he died of pneumonia, he was laid to rest at Zręcin’s cemetery, next to the Gothic Revival chapel that he had funded.

The invention of kerosene is still praised today. On April 22, 2015, in Łańcut, the street between the market square where Zech was born and Wałowa Street, where Łukasiewicz’s pharmacy was located, was named Ul. Łukasiewicza i Zeha (Łukasiewicz and Zech Street). On the 29th of October 2022, the Polish parliament established 2022 as the year of Ignacy Łukasiewicz: He belongs to an honourable group of Poles whose activities have left a great and positive impact on the development of our homeland, as well as the whole world – reads the resolution.