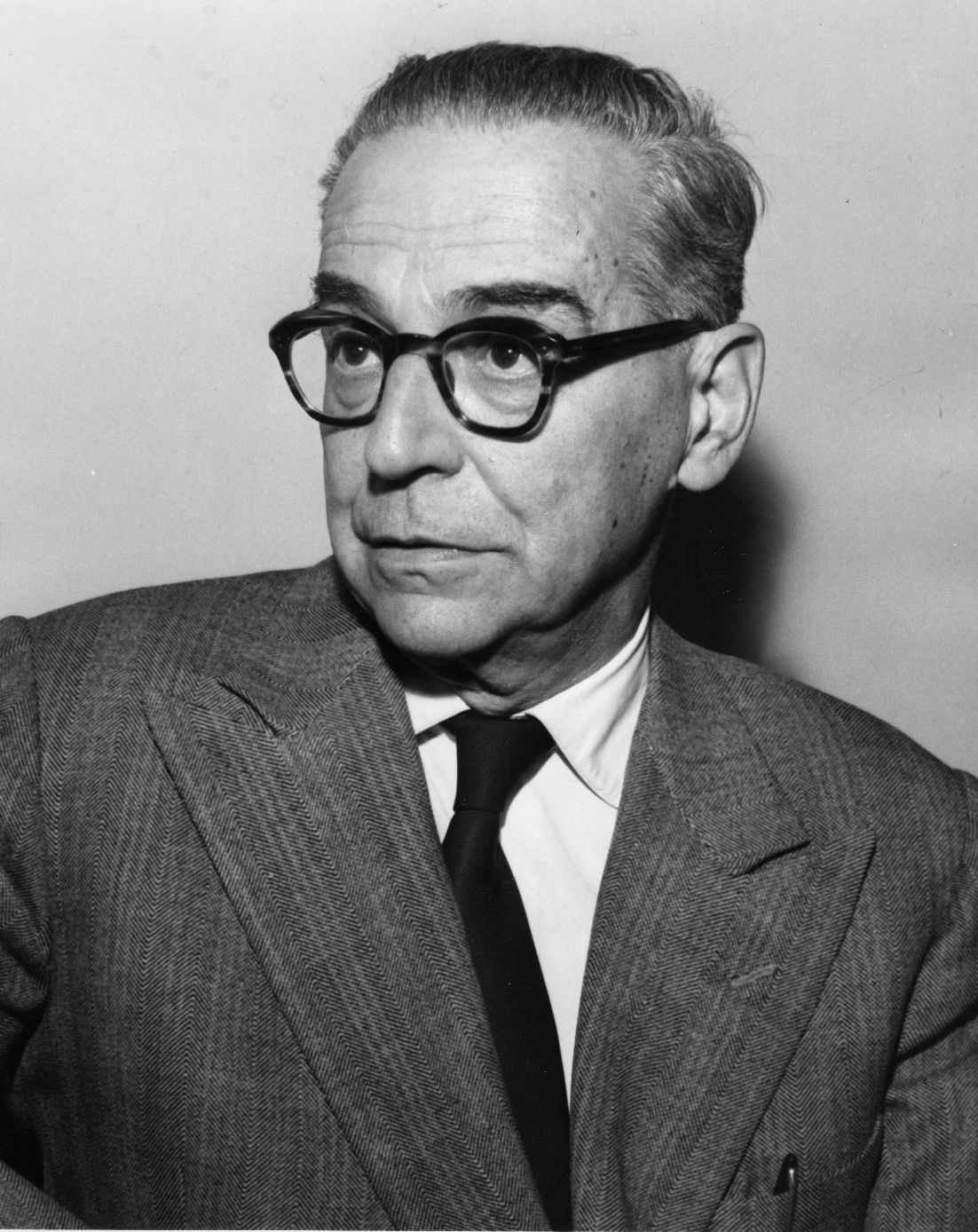

Most of the world knows Ivo Andrić as a Nobel Prize-winning author. However, to Habsburg administrators of his home of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Andrić was a teenage troublemaker suspected of collaborating in the assassination of Franz Ferdinand. We spoke to Enes Škrgo, curator of the Memorial House of Ivo Andrić in Travnik, the author’s birthplace, about his turbulent early years.

At the time of World War One, Austria-Hungary jailed Ivo Andrić. How did his political activism lead him into conflict with the government, and was he really close with Franz Ferdinand’s assassins?

Before the end of his life, he gave the Sarajevo author Ljubo Jandrić several statements in which he explicitly states his position on Austro-Hungarian rule over Bosnia and Herzegovina, including, “Us youth were irreconcilable opponents of Austria-Hungary, and for the uniting of all southern Slavs.”

As a secondary school student in Sarajevo, Ivo Andrić was one of those young people who formed what we today call Mlada Bosna, although to them, that name was unfamiliar. Its organizational form was most precisely defined by Andrić’s last biographer Michael Martens, who stated that it was a political current—not a movement, and definitely not an organization.

Their dissatisfaction with Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina had many reasons, one of which was the participation of students in the country’s social life. According to the Disciplinary regulations for high schools from 1908, students were banned from ordering political writings, participating in the work of any society, and founding societies themselves, except for student societies for assisting impoverished students. If they violated this regulation, students faced expulsion. They were banned from attending court hearings, political and public gatherings.

For that reason, students and other progressive young people in Sarajevo, Mostar and a few other cities resorted to forming secret societies. “At first those were literary circles which secretly gathered students so they could help each other,” said Andrić. “We Sarajevo students were against the hegemony of any religion or any nation. Our society had the name of Progressive Serbo-Croatian Youth, even though—on the other side—there were also reactionary secret societies that were gathering the youth. I wouldn’t like it to seem as if I am bragging when I say that I was the president of the Progressive Serbo-Croatian Youth in Sarajevo.”

What are some examples of Andrić’s more radical political activism?

When Slavko Cuvaj was named ban of Croatia in 1912, two-day-long student demonstrations erupted in Sarajevo, of which Andrić writes:

“When as a young student I bombarded - with thousands - the magistrate’s windows with rocks and in one unforgettable twilight held - while above me whistled bullets from the gendarmes - a young worker, who was dying without a voice and with bloody foam on his lips…”

Andrić was one of the members of the strike committee, and of that his mother Katarina said:

“He isn’t home for days. He comes a bit, he goes. He just grabs a piece of bread and flies out. He doesn’t say anything. Only later, and from other people, did I find out that Ivo was the ringleader of all of that.”

The student demonstrations resulted in the expulsion and deportation to their hometowns for ten students. At the train station the students organized a sendoff for their persecuted comrades and Ivo Andrić gave the farewell speech.

Austria-Hungary’s cultural policies in BiH was also one of the causes of progressive Bosnian and Herzegovinian youth’s antagonism towards the Monarchy. In the entire country at the time there were five preparatory secondary schools, there was not a single college or university, and in the capital city there was no public library. In the essay How I Entered the World of Books and Literature Andrić writes of his youthful troubles:

“Books, that was the big passion and big pain of our young years. It was and remained the yearning of my childhood. As a child in the third year of gymnasium, I was suffering from a real thirst for books. That thirst was that much greater because it was hard to reach books[…]

In our impoverished apartments there were no books, besides textbooks or some poor calendar. School offered little or nothing, and we couldn’t even speak about purchasing. In Sarajevo at the time there were three or four bookstores…the biggest and best “bookstore and stationery,” the property of some migrants, was the only one who, besides some of ours, had plenty of foreign books, in German, in a modernly arranged, well-lit window display.

I spent, in my early student years, many hours in front of that display.”

Why did Andrić ultimately end up in prison?

After the Sarajevo assassination, chained along with other arrestees, the Austro-Hungarian police took Andrić to Maribor, site of the most modern jail of the monarchy.

Andrić was arrested because of his poetry (My pen brought me to slavery! Says one character in The Damned Yard). One of the reasons that some biographers list is the political implication of the line When the king’s armies arrive from The First Spring Poems, as an allusion to the arrival of the Serbian army of King Peter.

Truthfully, in some of his writings you could find evidence of a hostile position towards the Monarchy.

One newspaper clipping could have served the prison investigators as evidence of possible involvement in the assassination. In the nationalist cultural magazine Vihor on the occasion of the death of A.G. Matoš, Andrić’s lecture in the Croatian student club Zvonimir was published. He said: “All of Croatia uglily snores. Only the poets and assassins are awake.”

The main reasons he was investigated were actually his acquaintance with Gavrilo Princip and the other participants in the Sarajevo assassination, and his participation in Mlada Bosna, to use this name.

“Once, in the Turkish cafe Kairo near Baščaršija, while we played pool,” said Andrić, “Gavrilo Princip came up to me with a plea that, since he also writes poetry, I look at his verse.” Andrić was already well-known among the students because of his poems published in the famous Sarajevo magazine Bosanska vila (Bosnian fairy).

Besides Gavrilo Princip, Ivo Andrić knew a few other assassins and their assistants, including Danilo Ilić, the main organizer of the Sarajevo assassination—in one letter, Andrić greets Hadžija, which was Ilić’s nickname. He dedicated the piece In the Street of Danilo Ilić to him.

However, about the preparation and execution of the assassination itself Andrić certainly was not notified, nor did he have any part in it, because at that time he was a student of Jagiellonian University in Krakow. Still, it is significant that on the night of June 28th, 1814, when he found out that some students in Sarajevo committed an assassination, he left Krakow on the first train, then arrived in Zagreb, then in Split, where he was arrested.

To what extent did Andrić’s political experience from youth later affect his writing?

In his prose, Ivo Andrić barely refers to his youth political experiences. The Damned Yard is most frequently cited as a partially autobiographical work, in which one tries to recognize the author’s prison experience during World War One. The author commented:

“Laying in the Maribor prison helped me draw the basic outline and shade the central throughline for this story. Some critics wrote: if there was no Maribor casemate, there would be no Damned Yard. That is beginning to resemble exclusivity. Prison helped me significantly to understand the world behind bars, condemned men, arrestees and insidious justice. Would there be Damned Yard if there wasn’t that mute and unfeeling cell in Maribor? I don’t know that, and the author is the least reliable source where you can check those things.”

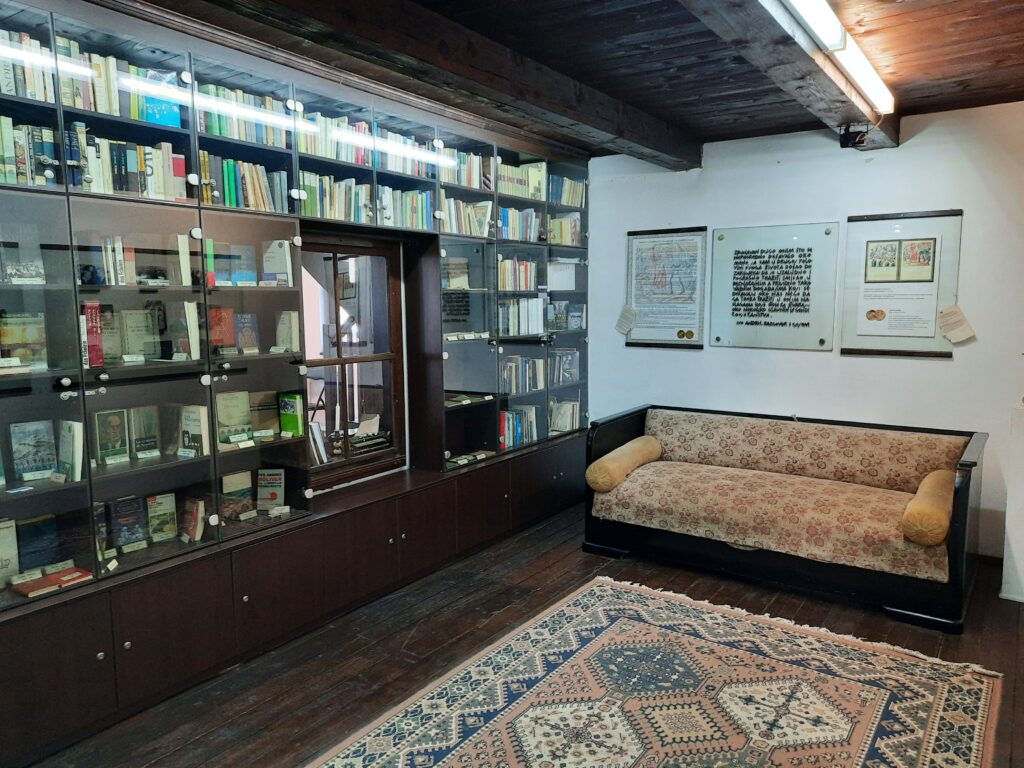

What can a traveler see in the Ivo Andrić House, especially from his early life?

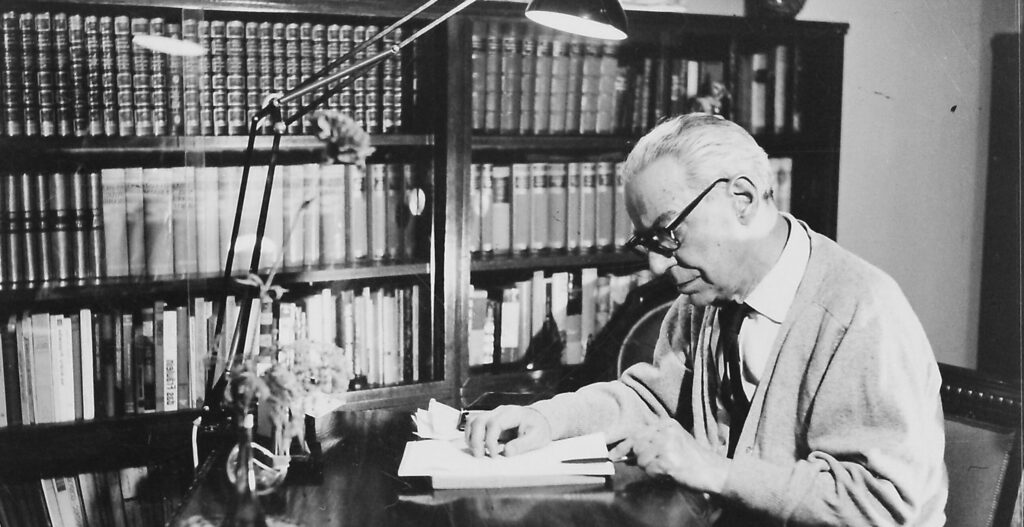

The permanent exhibit of the Memorial House of Ivo Andrić is focused on local elements from the life and literary work of Ivo Andrić, his Travnik prose Bosnian Chronicles and The Vizier’s Elephant, as well as Ex Ponto, parts of which wrote during a period of confinement in the village Ovčarevo near Travnik.

The interior of one room shows the living conditions in towns of Bosnia and Herzegovina at the end of the 19th century and contains furniture typical for the time of Andrić’s birth. Also interesting are the facsimiles of the reports that French and Austrian general consuls sent to their ministers and emperors from Travnik, which served as the main source for Ivo Andrić’s writing about that time.

The Memorial museum’s library has editions of Andric’s work from the whole world, in nearly 30 languages, including first editions of books and literary magazines.

In the room called Open Literary Atelier (where they hold literary and cultural events), during the Museum’s opening hours you can sit in the old armchairs and read the books of Ivo Andric, as well as global classics, local authors, literary magazines…

During the rehabilitation and reconstruction of Ivo Andrić’s Birthplace as a typical Bosnian residential home, we got a multifunctional space on the ground floor. In the central courtyard is the Restaurant and Bar “Ex Ponto,” named after Ivo Andric’s first book. There is also the Meeting place and Little Gallery “Ex Ponto,” where we regularly organize curated cultural events, academic conferences, chamber music concerts, lectures, exhibits and literary programs. Ivo Andric’s birthplace has become a lively place of culture and literature, with top-notch gastronomy.

This interview was translated and edited for length and clarity by Rebecca Duras.