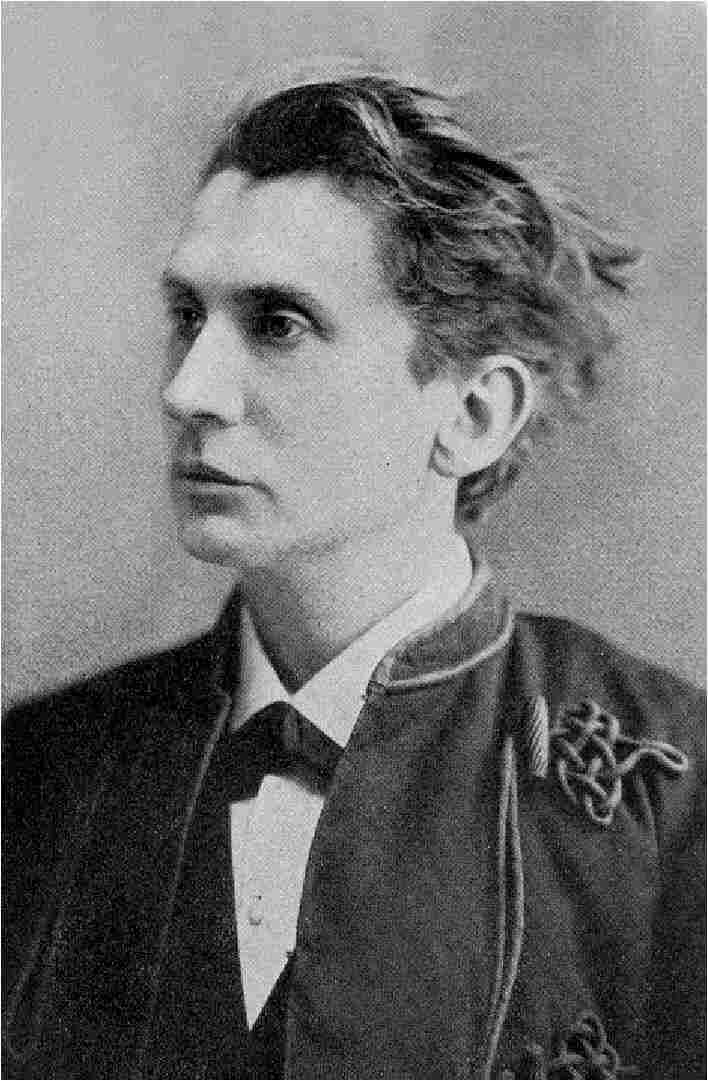

Have you ever wondered where masochism comes from? It started during the Habsburg Empire, in Galicia (which used to be a region from eastern Poland to western Ukraine). Leopold von Sacher-Masoch grew up there, raised by his Ukrainian nurse who has had a huge influence on him. She told him Ukrainians tales and sang to him popular songs from what was called at the time Little Russia. According to Leopold, her influence has had a great impact on who he was and on his work as a writer.

After obtaining a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Graz in 1856, he dedicated himself to teaching history. That year, he also began his literary career and wrote historical novels. The traumatisms he experienced as a young boy imbued his work. He spent his childhood in a police station as his father was a police chief in Lemberg (the German name of Lviv in Ukraine). He saw soldier-policemen capture vagabonds, delinquents in chains and the corporal punishment rooms; ‘God knows it was not a pleasant environment!’, he said.

Leopold was only ten when he saw the “bloodbath” as he called it that occurred in Galicia in 1846 during the violent rebellion of peasant communities against the nobles. Three of his books attest to this: The Mother of God (1883), Paradise on the Dniester (1877), and Peasants’ Justice (1877). Leopold was captivated by the persona of Polish peasant leader Jakub Szela in this revolt. He appears frequently in Sacher-Masoch’s works. Regarding this revolt, he stated he would never forget ‘the miserable little carts’ that carried the dead and injured; nor the dogs which licked the spilled blood.

While he was writing A Galician Story (1858), he claimed that an illness struck him which tormented him for years: he was homesick. ‘I have always had a religious and passionate love for this country, the love that the Slavs feel for their homeland. This little corner of the earth where I was born has always been like a mother to me, something venerable, holy,’ he said in one of his autobiographical works. He spent his first royalties to return to his homeland, where he began to ‘cry like a child’ when he recognised the places he grew up in, still according to his work.

Sacher-Masoch played a political role after the military campaign of 1866. He had defended the interests of his compatriots through his pen for years and after the Battle of Sadowa (or Königgrätz, in 1866 in which the Kingdom of Prussia defeated the Austrian Empire) he founded a newspaper taking sides against the pro-Prussian tendencies. Spiridon Litwinowicz who was Archbishop of Galicia and leader of the Little Russian Party, sent him a letter in which he placed himself and the Nation under Masoch’s protection.

Masoch was a well known and respected author. In 1886, he travelled to Paris, where the Figaro and the Revue des Deux Mondes praised and honoured him. He received the Legion of Honour there and published in the Revue des Deux Mondes and La Revue bleue. Sacher-Masoch’s most complete autobiographical texts appeared first in French translation and it was no coincidence. He did not like German. With the French translation Les Prussiens d’aujourd’hui, published in 1877, he made many friends in France. He was considered in Germany the ‘peak of what is to be hated and despised’. Making him a target of mockery.

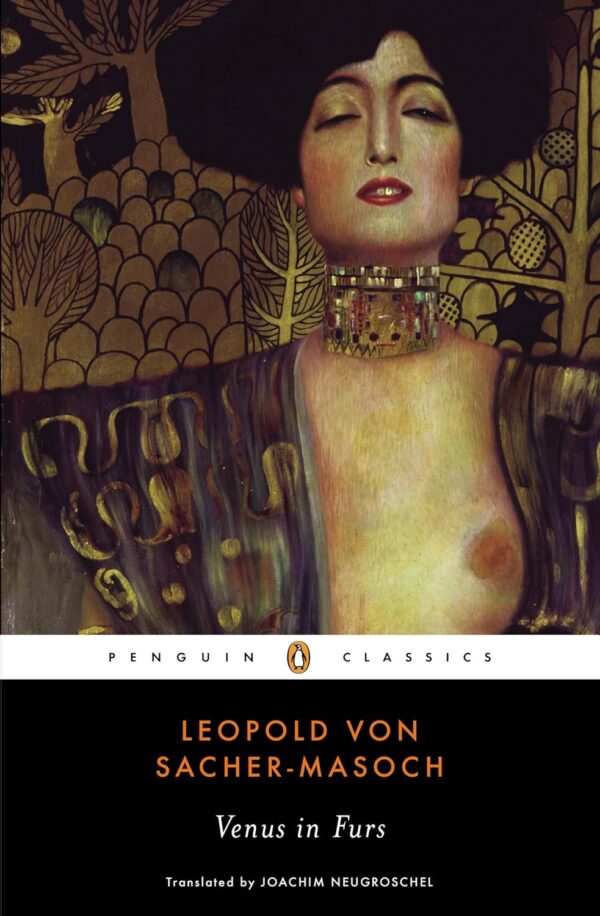

This can undoubtedly be explained by the publication of Venus in Furs, which is an erotic novel in which a Galician nobleman is the slave of a woman wearing fur. It is his most famous piece of work and was translated into several languages and constantly reissued. He was also disliked by Germans for his political position, which he expressed in The Ideals of our Time (1876). It was designated as the most ‘anti-German’ work in existence. ‘All that is mine I owe to myself … and to my enemies,’ said Leopold von Sacher-Masoch in his autobiographical texts.

The Austro-Hungarian psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing was the first one to use the term “masochism” to name what he considered a pathology. This made the name of Leopold von Sacher-Masoch famous as a concept, but his work as a writer was forgotten. At the end of the 1960s, the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze became interested in Sacher-Masoch again. Since then, a large majority of his novels and short stories have been republished and many researchers have commented on them.

According to Deleuze, Masoch’s writings are important and unusual. Masoch’s idea was to write a series of cycles. The main one is entitled The Heritage of Cain and was supposed to be composed of six themes: love, property, money, the State, war and death. Only the first two parts were finished, but we still can find the other four themes in his writings. The second cycle regarded folktales and ethnic tales. They included in particular two sombre novels (The Fisher of Souls and The Mother of God) dealing with mystical sects in Galicia which are still according to Deleuze among the best of Masoch’s works. They ‘reach heights of anguish and tension rarely equalled elsewhere,’ he said.

In Deleuze’s opinion, no other writer has used to such effect the resources of fantasy and suspense. He stated that Masoch has a particular way of ’desexualising love and at the same time sexualising the entire history of humanity’.

When it comes to issues of love, Masoch’s inclinations are well known: his Venus in Furs was fictional but was inspired by his own experience. He enjoyed dressing up as a bear or a burglar, being tied up and subjected to various punishments, humiliations and intense physical pain by his mistress who was wearing fur and brandishing a whip. Given Sacher-Masoch’s tendencies, it’s plausible that the more sinister aspects of police work in Galicia – bondage, incarceration, punishment, and particularly flogging – left a lasting impression on his impressionable young mind which later on impacted his sexuality. But let’s leave that to the psychoanalysts.

Masoch has endured unjust treatment as a result of his name being connected to a perversion (associated with Sade’s name to form the term sadomasochism). His name was not wrongly linked to masochism; rather, his contributions were overlooked as his reputation grew. Though there is the rare exception, it is less frequent to see pieces about Sade that show little acquaintance with Sade’s work. The recognition of Sade’s work is growing; literary assessments of his writings contribute significantly to clinical studies of sadism and vice versa. But to Deleuze, even the best studies on Masoch demonstrate an astonishing lack of knowledge of his work. The fact that sadism and masochism are today synonymous, as well as the concept of a sadomasochistic being, have caused great harm to Masoch. In addition to being unfairly neglected, he has also been wrongly assumed to be in dialectical unity and complementarity with Sade. Deleuze claims there is no connection between Masoch’s reality and Sade’s. Their methods are dissimilar, and they have completely different issues, worries, and goals. If you want to learn more about the difference between Sade’s and Masoch’s work, we advise you to check out Deleuze’s essay Masochism: Coldness and Cruelty (1967).

In this article from RFE/RL, Lviv tour guide Andriy Maslyuk was asked about Masoch’s legacy. He explains that Masoch is hardly acknowledged in the city of his birth, because his work is taboo in a nation where religious morality is still revered. “Because of the Iron Curtain here, many local heroes that didn’t fit with Soviet mentality were not promoted, and they ended up simply being forgotten,” Maslyuk said.

Several French historians and authors tried to restore Masoch’s image by focusing on his literary talent. To Bernard Michel, historian, Kafka even paid homage to Masoch in The Metamorphosis and not only by using masochistic themes. When Masoch travelled to Italy with Fanny Pistor, he dressed up as a servant and used the name Gregor. In The Metamorphosis, the protagonist is named Gregor Samsa. Samsa could also be an anagram of SAcher-MASoch. Bernard Michel believes that Masoch has his place in the lineage of the greatest writers of Central Europe (Michel, 1989). As for Jean Dutourd, author and member of the French Academy, Sacher-Masoch was an “endearing and curious author who had the audacity to write some extreme forms of love, a brilliant caustic mind, a sort of perverse poet à la Baudelaire” (Dutourd, 1986). Jean-Paul Corsetti, author, added that erotism in Masoch’s work “fully integrates into this kind of human comedy where fiction is at the service of a political and cultural, philosophical, aesthetic and spiritual commitment” (Corsetti, 1991).

Bibliography:

Jean-Paul Corsetti, Leoppold von Sacher-Masoch La dame blanche, préface. Édition Terrain vague, 1991 p.9

Gilles Deleuze, Présentation de Sacher-Masoch, Le Froid et le cruel avec le texte intégral de La Vénus à la fourrure, Éditions de Minuit, 1967

Jean Dutourd, Contre les dégoûts de la vie, Flammarion, 1986, p.99-101

Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, Écrits autobiographiques et autres textes, Éditions Léo Sheer, 2004

Bernard Michel, Sacher-Masoch. 1836-1895, Paris, Robert Laffont, 1989

Start your journey in the Extinguished Countries!

Get a free chapter from our first guidebook “Republic of Venice” and join our community!