Pasquale Revoltella (1795-1869) was a baron, economist and entrepreneur; but more than anything, a perfect specimen of the Habsburg self-made man. The son of a butcher, he built his fortune bit by bit until he reached the pinnacle of his career as vice president of the Suez Canal Universal Company, which opened in 1869. We talked about this incredible story with Pierluigi Sabatti, a journalist and writer from Trieste who has devoted years to the study of Baron Revoltella and in 2018 produced a podcast entitled “Baron Revoltella and the Suez Canal.”

“I have money in my head and not in my heart.” With this quote from Revoltella, Sabatti begins his narrative, anticipating the exciting events of a man who came from nowhere, built his economic empire until he reached the pinnacle of his career as vice-president of the Suez Canal Universal Company, obtaining the title of baron from the Austrian emperor. But before we delve into the baron’s biographical events, Sabatti takes us on an extraordinary journey through history to discover the forerunners of the famous work of the “Great Frenchman” Ferdinand de Lesseps, who designed the Suez Canal.

The idea of digging a canal to establish new routes to the East,” Sabatti says, “goes back millennia. As early as the time of the Egyptian pharaoh Sesostri III (1879 B.C.-1846 B.C.), the Pharaohs Canal connected the Nile with the Red Sea. Centuries later, when the Persian empire ruled Egypt, King Darius I produced a similar work as evidenced by some stelae found in the 19th century. Several times over the centuries this canal was re-excavated only to fall into disuse and fill up again over time. The work was repeated in the time of the Ptolemaic pharaohs and by the Romans under Trajan. Finally, after the Muslim conquest of Egypt in 646 A.D., the Pharaohs Canal was dug one last time only to be finally closed in 767.

We have no more news about the attempt to dig a canal until the early 16th century, when a document dated May 24, 1504 tells us of a Venetian embassy to the Sultan of Egypt for the very purpose of digging a new canal subsidized by the Serenissima. However, the initiative ended in a deadlock. The emperor of the French, Napoleon Bonaparte, also considered the idea of digging a canal, but a rough estimate of the height difference between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea convinced him of the need to build a system of locks, which would have driven up the cost, too much when compared to the limited profit the canal was believed to provide.

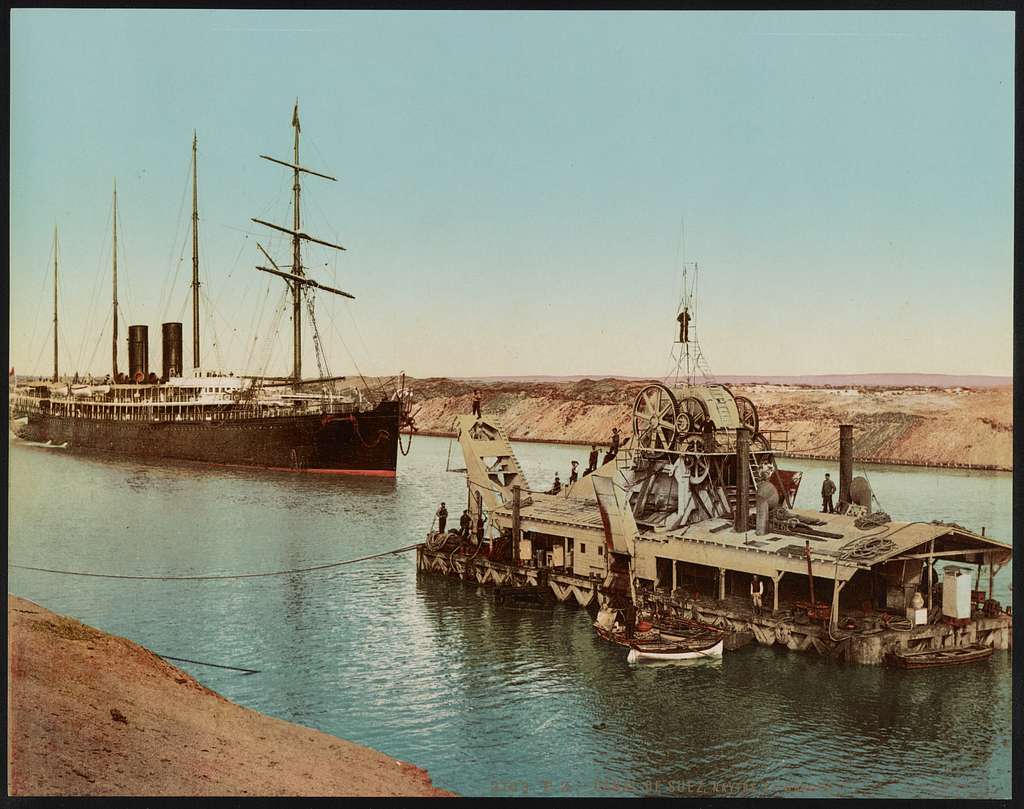

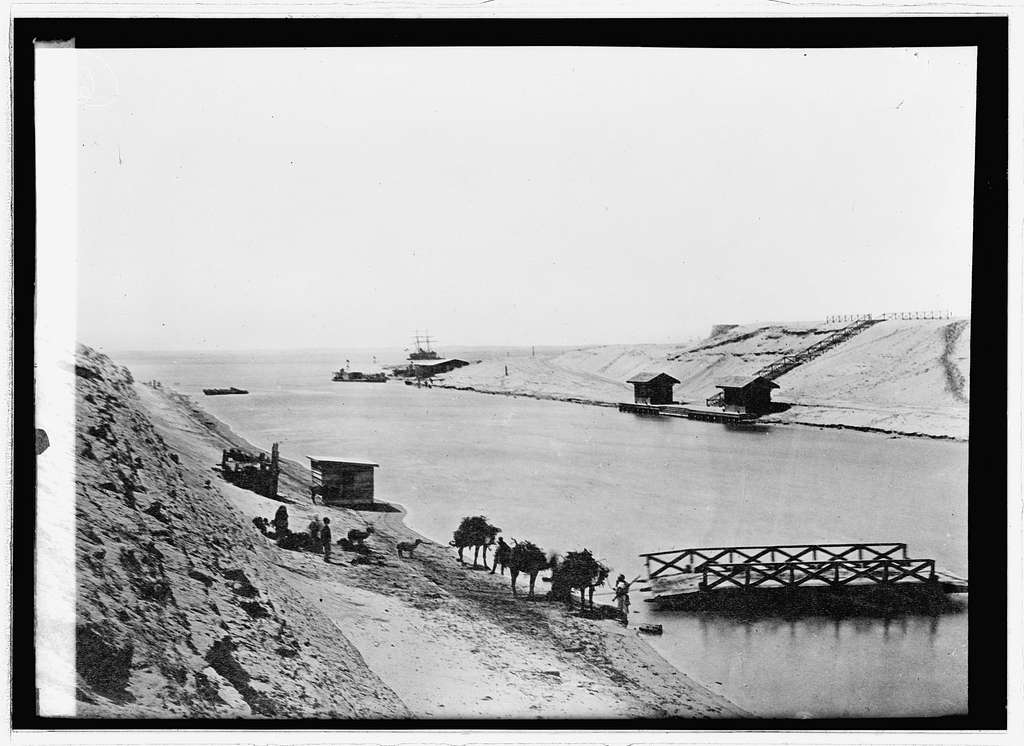

Thus, it was not until 1854 that Ferdinand de Lesseps, a French diplomat stationed in Egypt, obtained a concession from the chedivé (viceroy) of Egypt, Sa’id Pasha, to establish a company to excavate and operate the canal, guaranteeing its opening to ships from every nation. The project was entrusted to engineer Luigi Negrelli, and in 1858 Lesseps founded the Compagnie universelle du canal maritime de Suez. This is precisely where Baron Pasquale Revoltella, one of the most prominent entrepreneurs of mid-nineteenth-century Trieste, comes in.

So who was Pasquale Revoltella, and why is Trieste so important in this story?

Revoltella was born in Venice in 1795, the son of Giovanni Battista, a humble butcher. When he was just two years old, because of the inexorable decline to which the Republic was heading, his father decided to move with his family to Trieste, a growing city that was the nerve center of all the Mediterranean routes involving the empire of Austria. “Revoltella remembered this decision by his father as the best he had ever made,” Sabatti recounts. However, the father wanted his son to follow in his footsteps, while his mother, Domenica, who recognized the importance of education, did everything possible to allow her son to complete his basic education at the trivialschule.

After the early death of his father, the 13-year-old Revoltella began working at the trading firm of Swiss consul Teodoro de Necker. Proving himself capable and resourceful, he was able to climb the company hierarchy until he became a prosecutor. In 1835, thanks to the capital set aside during those years, he was able to establish his own lumber and grain import company. He entered the hierarchies of Assicurazioni Generali and the newly formed Lloyd Austriaco as a shareholder and began to participate in the city’s political life. During these years he met and became friends with Baron Karl Ludwig von Bruck, an Austrian diplomat and future finance minister of the empire.

Revoltella loved Trieste very much and dedicated numerous charitable and patronage works to his adopted city: he founded a drawing school, donated an altar to the church of Santa Maria Maggiore, promoted the construction of the Teatro Armonia and the Ferdinandeo Palace dedicated to Emperor Ferdinand I (1793 – 1875). In 1848, he was part of a delegation that went to Innsbruck to the Emperor of Austria, who was in exile there as a result of the uprisings that had shaken all of Europe that year. On that occasion he brought to the emperor the allegiance of the city of Trieste, which was granted great privileges, becoming an immediate city of the empire: it would enjoy great autonomy, and the city council would be replaced by a diet that answered directly to the emperor.

This was the Trieste that welcomed Ferdinand de Lesseps in 1859. The French entrepreneur had been invited the previous year to a meeting held in Paris to discuss Trieste’s participation in the project, specifically through Revoltella. De Lesseps and Revoltella reportedly discussed the agreement with representatives of the city and the governor of Lombardy-Venetia, Archduke Maximilian of Habsburg. For his key contribution to the project, the Trieste entrepreneur was thus appointed vice president of the Suez Canal Universal Company.

But 1860 was an inauspicious year for our future baron: he was indicted and imprisoned because of serious allegations of wrongdoing. According to the indictment, Revoltella speculated on military supplies destined for Austria, which decreed the severe Austrian defeat at the Battle of Solferino (June 24, 1859) during the Second War of Independence (April-July 1859). Revoltella was soon acquitted but the affair still had a nefarious outcome: Baron von Bruck, accused with him, took his own life. Revoltella continued his work, however, largely financing the excavation of the canal, and his name was fully rehabilitated when Emperor Franz Joseph gave him the title of baron in 1867.

On November 17, 1869, to the sound of the Egyptischer-Marsch (Egyptian March) by Johann Strauss (namesake son of the more famous composer), a solemn ceremony decreed the opening of the Suez Canal. The inauguration was attended by French Empress Eugenie, Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria, the Egyptian chedivé, and the royal princes of Prussia, the Netherlands, and the Russian Empire. All those who had dreamed of the canal saw it finally realized, but one person was missing from the roll call: Pasquale Revoltella could never witness the spectacle of the ships of the great rulers of Europe reaching the Red Sea directly from the Mediterranean for the first time. In fact, the baron had passed away just two months earlier at his villa at Cacciatore in Trieste after a long illness.

Although today the figure of Revoltella does not enjoy great celebrity, the city of Trieste, albeit unwittingly, still preserves his priceless legacy. In fact, the baron, dying without an heir, left his property and fortune to the city to set up a museum. Today the Revoltella Museum is housed in the baron’s city palace and features a splendid collection of modern artworks, some of which came from his private collection and some of which were purchased later. Before saying goodbye, Dr. Sabatti makes an invitation to us: he invites us to always be curious since, in his own words,“as long as you are curious, you are alive.”

Start your journey in the Extinguished Countries!

Get a free chapter from our first guidebook “Republic of Venice” and join our community!