It all began in 1772, when the Treaty of Petersburg sealed the partition of Polish territories between the three major European powers of the time: in other words, Prussia, the Habsburg Empire and Russia. This was the first of three partitions that ended the Polish-Lithuanian Confederation in 1795. The aim of the treaty was somehow to restore the balance in Europe, previously unbalanced in favour of Russia, which had a strong influence on the Polish-Lithuanian Confederation and had won the so-called Russo-Turkish Wars (1768-1774). As a result of the partitioning of the Confederation, Maria Theresa’s Empire broadened its borders to incorporate parts of today’s Ukraine and Poland, in what became known as the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, or more generally Galicia.

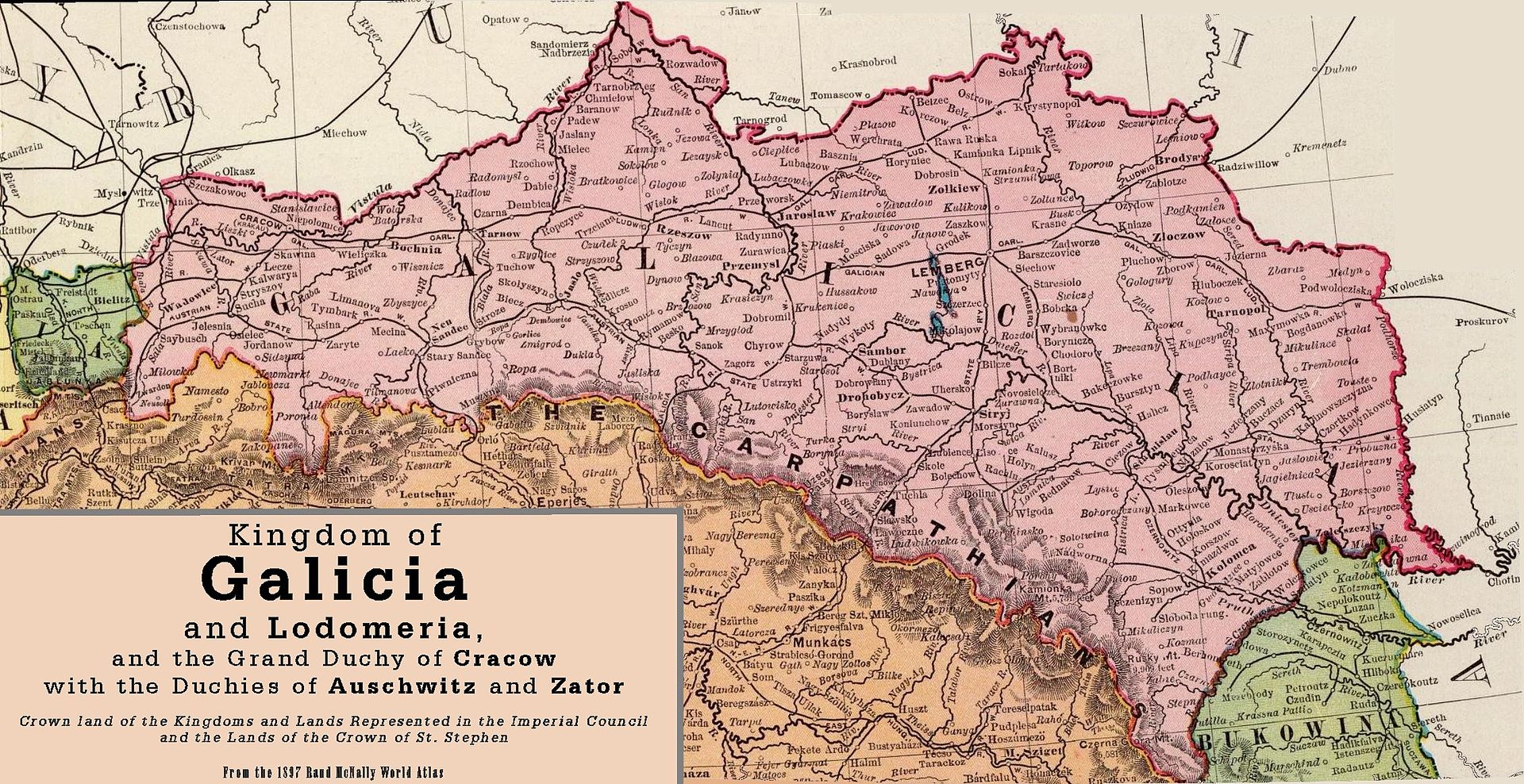

From 1772 to 1918, this province stretched from Cracow to Kolomyja via Lviv, and owes its name to an important mediaeval settlement, Halyč (transliterated as Galic) today a town in western Ukraine located along the Dnestr river. Under Habsburg rule, Galicia enjoyed a period of economic and cultural development. The peasant component of the population, for instance, benefited from innovations in farming techniques but also in terms of freedom, seeing the corvée finally abolished.

The education sector was also reformed and improved, allowing, among other things, the possibility of teaching in the Ukrainian language.

In the 19th century, however, Galicia’s population also experienced violent rivalry between the Ukrainian minority and the Polish majority. The latter consisted mainly of landowners and governors, so that even in those areas where ethnic Ukrainians made up the majority of the population, the administration remained in Polish hands. The Habsburg authorities did little to balance the situation; on the contrary, there was clearly a pro-Polish bias in imperial policies. Despite this, under the rule of the Empire, Ukrainian (or rather, as it was then called, Ruthenian) society enjoyed a good deal of cultural autonomy, which was not granted to the Ukrainians of Tsarist Russia.

After Poles and Ruthenians, the third largest ethnic group was the Jews, whose numbers grew to almost double during the Habsburg rule. The Jews of Galicia lived in small, picturesque villages, the shtetl, where they mainly worked as merchants. Over the years, however, Galicia’s Jewish component also came to occupy many state offices, so much so that at the turn of the 20th century, Jews made up 58% of the province’s civil officials and judges.

Galicia was thus a multi-ethnic region within a multi-ethnic empire, and this peculiarity was noticed even back then. Bruno Schulz, one of the most famous writers of the time in fact wrote in his memoirs:“I am a public employee, an Austrian, a Jew, a Pole – all at once within an afternoon”

The words and lives of Galician authors are one of the best gateways to the culture and history of this province and allow us to step back in time and almost experience the atmosphere that existed then.

In order to tell the story, I decided to ask an expert for help. Eugenio Berra is the founder of Confluenze – Nel sud-est Europa con lentezza and contact person in the Balkans of the sustainable tour operator Viaggi&Miraggi. Since 2019, he has been organising tours to discover Galicia, unfortunately suspended by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Eugenio knows about the article I am writing, and answers the phone eagerly, immediately jumping into the story of Schultz’s life. “Bruno Schulz was born in 1892 in Drohobyč, a town in the Lviv oblast, into a Polish-speaking but Jewish family. His stories are permeated with magical realism, and tell of childhood myths, his relationship with his father and work in the small shtetl workshop. Schulz would only develop a relationship with his religion at the age of more than 30, unfortunately shortly before the arrival of the Nazis, by whom he would be killed in the ghetto of his hometown in 1942” says Eugenio.

Our conversation naturally leads us to Lviv (or Lemberg), the capital of the Ukrainian part of Galicia. Eugenio tells me how writers of the time could not help but write about Lviv, such was their fondness of it. “Joseph Roth gave a beautiful definition of Lviv as a city with canceled borders” he explains, “Roth was born in Ukraine in the late 19th century to a Jewish family. And to the Jews of Galicia he dedicates a splendid book, ‘The Wandering Jews’, in which he recounts life in the Galician shtetl, inhabited at the time by eighty percent Jews.”

I learn from Eugenio’s words that Galicia was certainly the birthplace of many men of letters, but not only. “There are various treats associated with Galicia, especially in Lviv. One of them is the Scottish Café. The Scottish Café” Eugenio continues, “was the meeting place of the mathematicians of the Lviv School. Once at the café, one of them would issue a challenge, a mathematical problem, and the others would try to solve it. To write down their calculations they used whatever surface was at hand, even the tablecloth. But most of the solutions were written down in a large common notebook, the ‘Scottish Notebook”.

As if this story was not already exceptional, I also discover that a copy of the notebook is still preserved inside the building that once housed the Scottish Café, where the Szkocka (Scottish) Restaurant stands today.

The conversation could go on for hours, but in order not to detain our guest any longer, I allow myself just one last question. I ask Eugenio to reveal his favourite quote, the one that you’d like to write on your hand so you won’t forget it.

“Definitely the lines from “to Go to Lviv”, one of Adam Zagajewski’s most beautiful poems. Even if you need your whole arm to write it” Eugenio replies amused.

I don’t have a whole arm at my disposal, but I’ll leave my very favourite passage here:

“and there was too much

Lviv, it didn’t fit on the plate,

it burst the glasses, it overflowed

from ponds and lakes, smoked from every

chimney, it changed into fire, into a thunderstorm,

laughed with lightning, became docile,

returned home, read the New Testament,

slept on the sofa beside the Carpathian carpet,

there was too much Lviv and now

there is no more, […]”

Start your journey in the Extinguished Countries!

Get a free chapter from our first guidebook “Republic of Venice” and join our community!