Imagine walking along a road that crosses rural Japan and takes you through 69 post towns, where merchants, samurais, monks and travelers once used to stop by. All around you, artifacts, buildings and landscapes recount the story of Japan and how its unique identity was gradually formed. You wander through the country and dive at the same time in a distant past.

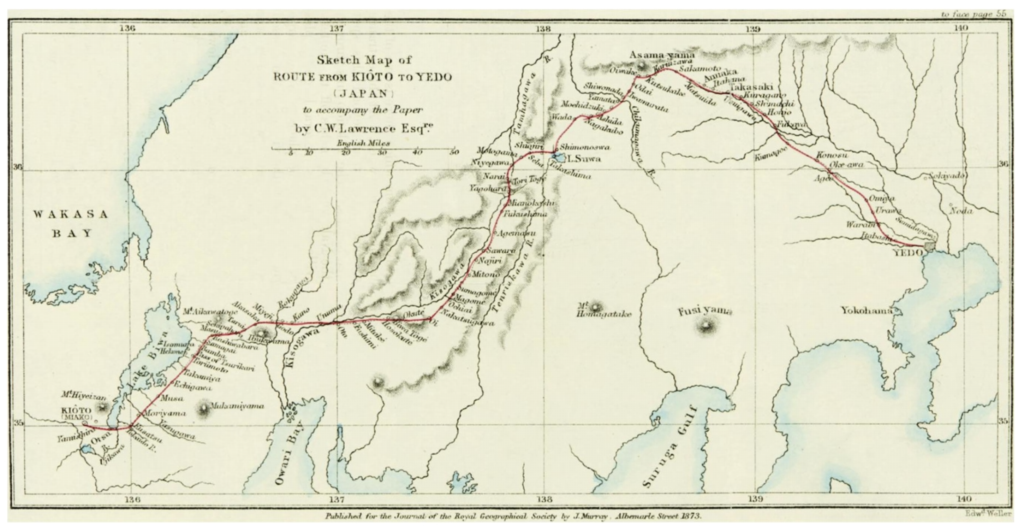

This road is the Nakasendo – the “Central Mountain Route” as the Japanese name indicates – and it stretches over 500 kilometers from Tokyo to Kyoto. It was built in 1603, at the beginning of the so-called Edo period, when Japan was ruled by a Shogun and the capital of the country was moved from Kyoto to a place called Edo and now known as Tokyo.

Two experts of Japan’s history and culture have recently embarked on a journey to (re)discover the Nakasendo. They are walking along this route, interviewing people and taking notes. Their goal is to provide the first up-to-date, interactive guide to this amazing and quite forgotten historic road. Their names are Frank and Carrie Lange and this is their story.

Frank and Carrie, can you help us understand what Nakasendo is, and in what historical context it fits?

In short, Japan was unified prior to somewhere after the 1300s. And then it sort of fell apart. The governance of the country was really driven by around 200 to 300 “daimyos,” which were basically Lords of specific provinces under their control. For 150 years, they basically fought each other indiscriminately, causing huge amounts of bloodshed and loss, famine, and all sorts of issues throughout the entire country.

Around the later 1500s, three individuals, specifically 3 daimyos, were really instrumental in bringing that period to a close. And one of them ended up being pretty empowered in Japan in 1600. His name was Tokugawa. The first thing Tokugawa realized he needed to do, given all these different domains and everything being split up, was to find some way to link the country and project his power. But they also needed a way to drive a sense of unity in this country that, for so long, had been separate.

So the first thing he did was he proclaimed in 1603 that there would be five major highways throughout Japan. There would be the two main ones, which are the Tokaido and the Nakasendo (both connecting Tokyo to Kyoto). The Tokaido ran across the southern seacoast, and then the Nakasendo ran through the mountainous spine of the country. There were also three other smaller roads, but these were the primary ones.

Why were these roads so important?

Because they allowed people who had lived separately all this time to really start understanding what it meant to be Japanese, to understand the diversity in their culture. The government’s attempt was to bring them together into one homogenous group, promoting communication through economic means, political means, and also to control the movement of potential troops to make sure they protected their capital.

At that time, you had the Shogun who resided in Edo, which is now Tokyo. That was the Tokugawa capital. And then in Kyoto, the Emperor lived. The Emperor had really no political power whatsoever. He was more of a figurehead and had given control to Tokugawa, who held the title of the Grand General to suppress the barbarians, a very honorific, flowery title. Essentially, he was the martial leader, the military leader in the country, and that period lasted for 250 years.

What happened along with that, which is also very important, is that in the early 1600s, Tokugawa closed the country off to all foreigners, except for one Dutch settlement in the southern part of the country. So for 250 years, Japan was essentially closed off to the rest of the world. This allowed Japan to develop a truly unique and uncorrupted culture, which is what really makes this country so different from the rest of the world.

Could you give us some examples?

This 250-year period was pivotal in shaping Japan as it exists in people’s imagination. It gave birth to Kabuki (a classical form of Japanese theater), art, and all the things we associate with classic Japanese culture, including their traditional clothing and cuisine. Today’s Japanese cuisine, for example, started during the Edo period. It began with the way they sourced fish for the daimyo. They call it “Edo-sushi.”

Many aspects of food and clothing also underwent significant changes during this time. The clothes changed, Kimonos became accessible to the common person, and they weren’t just wearing wool, or cotton and indigo, but they were able to wear silk as well. So in the end, people had access to a lot of things that were only reserved for the royal family before.

As we said, the period we are talking about is the so-called Edo period. Traditionally it starts in 1603 and ends in 1868. What happens then?

In 1853, five US warships arrived in Tokyo Bay led by Commodore Matthew Perry with the mission to open relations with Japan for trade. This event caused a significant weakening of the government which had been declining in popularity for some time. In 1868, Imperial forces loyal to Emperor Meiji, toppled the Tokugawa shogunate, initiating the Meiji Restoration, marking the beginning of modern Japan as we know it today.

The new rulers wanted to distance themselves from what they perceived as barbarism and backwardness. They aimed to embrace modernity, Westernization, wearing Western clothes, having a Western-style army, and adopting a Western-style government. So, they tried to bury this history – the story of the Edo period – for years, to the point that even many Japanese don’t fully understand it. When we talked to our Japanese friends and asked, “Do you know about this history?” They would often look at us, saying, “I have no clue what you’re talking about.”

Could you give an example of a story that one can find along the Nakasendo?

There’s one particular rock in a section that was really important, related to the princess we’ve been following, which was a significant figure. She stayed in various towns, and they’re all proud of the fact that she stayed there. Most of the buildings have been restored or feature something to commemorate her stay. However, in one town, when she was 14, something significant happened—she had her first menstrual period. So, they buried the belongings she left behind and created a small shrine for it.

Just imagine it: two maids and maybe a guard or something, stood there, pondering what to do with it, discussing it for about an hour. Finally, they decided to place it in the garden and create a little shrine on top of it. They call it the “Moon Shrine.” We initially thought there was an inscription, and we searched everywhere for this infamous rock. We spent an hour on it until we finally went to ask the lady in the nearby tourist agency office. She confirmed that the rock we suspected was indeed the one. Sometimes, you just need that little clue, and you can’t quite figure it out on your own.

This leads you into the story of a 14-year-old girl who was forced to travel the entire breadth of the country to marry the Shogun of Japan, attempting to mend the collapsing realm. It’s a very human story, infused with humor and society. This story is the kind that we want to incorporate to provide not only historical context but also the context of humanity. Prior to this period, most of these people were confined to their domains due to warfare, civil war, and terrible battles that raged throughout the entire country. Now, as they traverse this road, they suddenly discover their country, themselves, and their culture. That’s the type of story we emphasize to draw people in and say, “This isn’t just a treasure hunt, there’s a lot more going on here.” There were tremendous human stories unfolding at the same time, and that’s what we’re trying to tell..

Carrie Turney Lange

Carrie earned an undergraduate degree in Linguistics and a master’s degree in Asian Studies focusing on the evolution of small to medium enterprises in Japan while working for a company in Tokyo in the late 1980s. Carrie has been a regular visitor to Japan through business and personal travel and, besides a lifelong love for Japanese history, food, and culture, has a passionate interest in Japanese art, textiles, and ceramics. Carrie is proficient in both spoken and written Japanese and is currently based in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Frank Lange

Frank earned an undergraduate degree in International Relations with a minor in Japanese history and a master’s degree in Asian Studies focusing on post-war economic relations between Japan and China. Having lived and worked in Tokyo in the 1980s, he has continued to be a regular visitor for both business and pleasure over the last 33 years. Following a successful 30-year career as a senior business executive focused on Japan and Asia, he is now a photographer and writer living in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

This is the end of The Nakasendo Project [Part 1]. Click the button on the right to read Part 2!

Start your journey in the Extinguished Countries!

Get a free chapter from our first guidebook “Republic of Venice” and join our community!