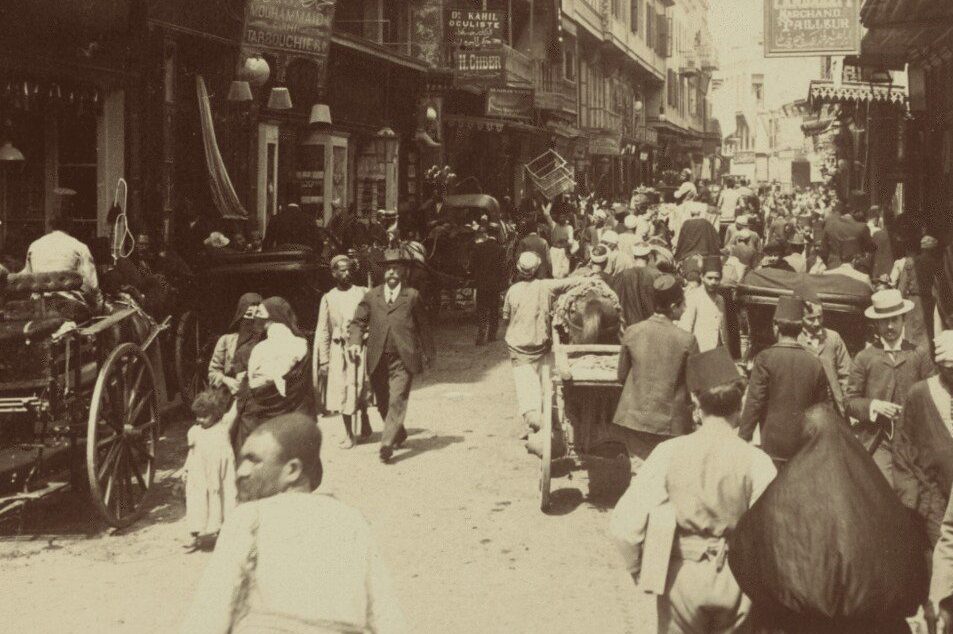

Let us imagine that we are taking a journey back in time, traveling to 20th century Egypt. Wandering the streets of Cairo and Alexandria back then meant bumping into numerous European officials, businessmen, and sophisticated ladies, all dressed in fine clothes and flanked by servants. Having passed the bazaars, noisy and overflowing with the aroma of spices and incense, we might stroll through the green public parks, where it would not be uncommon to see baby carriages pushed by young women of white complexion, dressed in exquisite dresses of satin, lace or silk. They were the Aleksandrinke and today we’ll tell you their story

On November 17, 1869, in front of three large grandstands packed with European officials and Ottoman dignitaries, the Suez Canal, the greatest engineering feat of the 19th century, was inaugurated.

For the first time, the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean were connected by a single waterway, and the journey to India, hitherto made in many months, became a matter of a few weeks. Egypt then found itself at the center of the world’s economic interests, attracting officials and wealthy businessmen from all over Europe who, in addition to their businesses, were also accompanied by their wives and children.

This sudden wave of migration did not affect only the highest bourgeoisie; in fact, it was accompanied by a silent multitude of salaried personnel. Prominent among them, in the roles of cooks, nannies and housekeepers, were women from the southern territories of the Habsburg Empire, such as the Vipava Valley, Gorizia and the Karst, who for more than a century, between the mid-nineteenth century and after World War II, migrated en masse to Egypt in search of better living conditions.

Also known as Goriciennes, Slaves and Slovènes, were known to be clean and tidy and at the same time sunny and motherly, more “Mediterranean” than their strict Northern European counterparts. Life in the countryside had accustomed them to pragmatism and hard work.

Moreover, belonging to the Habsburg Empire guaranteed them a much higher than average level of education, making them coveted professional figures even among the most distinguished clientele. Although the mother tongue of these young people was generally Slovenian, coming from a multi-ethnic and multilingual empire such as the Habsburg Empire, they often also spoke German, Friulian, and Italian (or the dialect of Trieste); moreover, in Egypt it was not uncommon for them to also learn English and French and sometimes even Greek and Arabic!

But why leave their home? Why go so far away to an unknown land? Leaving newborn children without a parent to go overseas to nurse other people’s children?

S trebuhom za kruhom, it was said, i.e. “to seek one’s fortune”. It was but that: they left in search of better conditions. For the sake of the family, these women would pack their bags, travel to Trieste and from there take a steamer that would take them far away, hoping to offer a better life to those they left behind.

Egypt must have seemed like another world to these women: the cities were metropolises brimming with life, the streets were bustling and the stores stocked by the boutiques of Paris and London.

The mansions where they served were equipped with conveniences unthinkable for Slovenian women, such as indoor bathing, running water and electricity, which introduced the Aleksandrinke to the wonders of the 20th century. All these comforts, combined with a salary about four times higher than they could have aspired to in Europe, were not enough, however, to make them forget their home; the homesickness was strong, and only together were these women able to find the courage to continue on the path they had taken.

With the valuable contribution of the order of Franciscan School Sisters of Christ the King., a chapel had been set up in Alexandria, dedicated specifically to Slovenian women, with an image of the Virgin from Sveta Gora, the sacred mountain of Gorizia.

In addition, at the end of the nineteenth century, an association was founded: the Slovenska palma ob Nilu, “the Slovenian palm tree on the Nile,” to provide support to the many women who had left home to find work. The association also took charge of women who arrived in the country still without a profession by establishing a kindergarten: theAzil Franja Josipa, “Franz Joseph’s kindergarten,” also included a Slovenian school, a kindergarten, and a library.

The meetings were intended to make the Aleksandrinke: Slovenian folk songs were sung, books were read, masses were attended in Slovenian, and small plays were staged. On these occasions they exchanged news from home and, in their blackest moments, sought the comfort and support of friendly faces who could understand homesickness and loneliness, feelings that must not have been foreign to these women, forced by necessity to leave everything they knew for the unknown.

During the atrocious years immediately after World War II, when Gorizia was the southern offshoot of the Iron Curtain dividing Europe, the steady flow of money sent by the Aleksandrinke most likely enabled them to wrest untold numbers of their countrymen from starvation and disease.

Yet in spite of everything, for most of the second half of the twentieth century, these women were treated with distrust and disapproval rather than gratitude. Upon their return, they were met with suspicion and disapproval. They were accused of abandoning their children and forgetting traditions. They were also accused of leading a dissolute life: the fine clothes, handbags and ornate caps would be evidence of this debauchery, as well as the languages learned (including Arabic) and the new habits acquired in those remote lands. Indeed, in the bigoted fantasies of their fellow citizens who remained at home, Egypt was a place of perdition, of physical and mental debauchery, a place that would certainly lead the young and inexperienced Slovenian women who took to the sea into temptation.

Although the history of the Aleksandrinke is not well known, Slovenia, which became independent in 1991, in search of virtuous models of patriotism, has recently rediscovered the stories of the Slovenes of Egypt. Books and films, in-depth features broadcast on public television and academic research were then dedicated to the Aleksandrinke. Their experiences have crossed the threshold of classrooms. Women who were once stigmatized have been elected as role models, have become part of the national mythology.

Article by Dario Trevisan

Would you like to learn more about Aleksnadrinke?

A documentary is available here!

Start your journey in the Extinguished Countries!

Get a free chapter from our first guidebook “Republic of Venice” and join our community!